Today's post is ALL about hairworms. I never knew how awesome they are until now!

By default, diagrams are from Thorp and Covich’s Freshwater Invertebrates, Chapter 15 Phylum Nematomorpha.

Before they are mature, the hairworms look white, as shown in this figure. A female Gryllus firmus which died 20 days postexposure to cysts of P. varius. Note the white color of the immature worms, which fill the entire hemocoel [insect blood circulation organ] of the cricket.

The next sequence of pictures shows mating hairworms.

(a) Numerous individuals of C. morgani forming a Gordian knot while attached to a stick. Scale bar = 1.0 cm.

(b) A male G. cf. robustus in the process of gliding along a female’s body. Note the spread tail lobes of the male.

(c) A sperm drop deposited by a male G. cf. robustus on the cloacal region of a female. Scale bars in B and C = 2 mm.

(d) A male Neochordodes sp. wrapped around a female and after depositing a sperm drop on the female’s cloaca. Scale bar = 2 mm.

By default, diagrams are from Thorp and Covich’s Freshwater Invertebrates, Chapter 15 Phylum Nematomorpha.

The lifecycle of hairworms

For hairworms raised in the lab, the entire life cycle takes 4–8 weeks, depending on the species.

A graphical summary of a typical hairworm lifecycle:

|

| Figure 15.6 |

- In water, an egg hatches into a hairworm larva.

- The larva eats tiny food debris, swimming freely in water.

- The larva gets eaten by a cricket larva.

- The hairworm larva leeches off the cricket and grows up.

- The cricket is all grown up, and so is the hairworm. The hairworm hears the calling of the water.

- The hairworm mind controls the cricket to jump into the water. Then in 30-60 seconds, the hairworm emerges and swims away. The cricket might survive this ordeal, feeling a deep emptiness inside.

- The hairworms mate in water and lays eggs.

They can mind control crickets

This is their source of fame. They do it to make sure they won't dry out after they escape the cricket.

You can think about this in another way: the cricket is actually an intermediate host, and the water is the final host. The hairworm controls the cricket to get willingly eaten by the water, then the hairworms emerge and mate in the body of the water.

The water is an apex predator: it can eat all kinds of species, even humans, by suffocation.

The knot of hairworms

Hairworms are also known as horsehair worms, nematomorphs, and gordiids. "Nematomorph" refers to how they look similar to nematodes. Nematodes (aka "roundworms"), by the way, are EVERYWHERE.

Hairworms are called "gordiids" because the adult worms often congregate in massive writhing orgies of hundreds, looking like a "Gordian knot".

Adult hairworms congregate into gordian knots while in water. The hypothesis is that they do this so that they would easily attach to floating debris on the water, rather than attach to dry land out of water. They do this to avoid drying out.

They can get so impatient as to start knotting before fully emerging from a cricket!

A female Gryllus firmus submerged in water for 30 s, from which a large number of worms are emerging. Note that worms begin forming Gordian knots even before they completely emerge from the cricket. Scale bar = 1.0 cm.

Hairworms are called "gordiids" because the adult worms often congregate in massive writhing orgies of hundreds, looking like a "Gordian knot".

|

| No relation to Haken's knot, though |

Adult hairworms congregate into gordian knots while in water. The hypothesis is that they do this so that they would easily attach to floating debris on the water, rather than attach to dry land out of water. They do this to avoid drying out.

|

| Figure 15.1, a typical gordian knot of hairworms. |

They can get so impatient as to start knotting before fully emerging from a cricket!

|

| Source: Wikimedia |

A female Gryllus firmus submerged in water for 30 s, from which a large number of worms are emerging. Note that worms begin forming Gordian knots even before they completely emerge from the cricket. Scale bar = 1.0 cm.

|

| Figure 15.8 |

Before they are mature, the hairworms look white, as shown in this figure. A female Gryllus firmus which died 20 days postexposure to cysts of P. varius. Note the white color of the immature worms, which fill the entire hemocoel [insect blood circulation organ] of the cricket.

|

| Figure 15.8 |

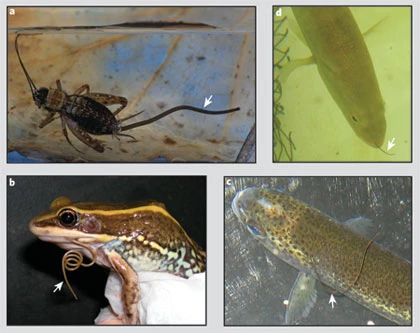

The next sequence of pictures shows mating hairworms.

(a) Numerous individuals of C. morgani forming a Gordian knot while attached to a stick. Scale bar = 1.0 cm.

(b) A male G. cf. robustus in the process of gliding along a female’s body. Note the spread tail lobes of the male.

(c) A sperm drop deposited by a male G. cf. robustus on the cloacal region of a female. Scale bars in B and C = 2 mm.

(d) A male Neochordodes sp. wrapped around a female and after depositing a sperm drop on the female’s cloaca. Scale bar = 2 mm.

|

| Figure 15.9 |

This figure shows two fossilized hairworms!

(a) The oldest known hairworm fossil, Cretachordodes burmitis recovered from Early Cretaceous amber (100 million years old) from Burma.

(b) Two specimens of Paleochordodes protus in the process of emerging from a cockroach hosts in Dominican amber (15–45 million years old).

This photo is pretty pointless for illustrating biology, but it feels dramatic, like a triple murder mystery in a sealed room...

A female ground cricket, Gryllus sp. which apparently died while feeding on dead midges (Chironomidae) and from which a P. varius attempted to emerge but also died. Scale bars = 0.5 cm.

|

| Figure 15.7 |

They can escape predators after being eaten

Hairworms have a life cycle that passes by just one host: the cricket. It's meant to escape the cricket into water and mate there. However, sometimes the cricket gets eaten. How is the hairworm supposed to escape?

Thorp and Covich, page 320:

Other studies by Ponton et al. (2006a,b) indicate that when infected orthopterans are consumed by aquatic vertebrates, a considerable number of hairworms (18–35%) can escape the predators of their hosts. Worms usually escape from fish predators through the mouth, nose, or gills and through the mouth from frog predators

|

| Figure from Parasite survives predation on its host (2006) |

This article has three supplementary videos. The first is the rather famous one where a hairworm swims out of a cricket that has suicided in a swimming pool, but the next two are astonishing...

This video shows a gordian worm escaping through a frog's mouth (Rana erythraea).

And this shows one escaping a trout's gill (Oncorhynchus mykiss).

Hairworm anti-predator strategy: a study of causes and consequences (2006)

Following the ingestion of the insect host by fish or frogs, the parasitic worm is able to actively exit both its host and the gut of the predator... the existence of an intense muscular activity in escaping worms, which functions in parallel with their distinctive biology... Remarkably, the number of offspring produced by worms having escaped a predator was not reduced compared with controls.

No comments:

Post a Comment