At its core, the Anthropocene is an encapsulation of the concept that modern human activity is large relative to the basic processes of planetary functioning, and therefore that human social, economic, and political decisions have become entangled in a web of planetary feedbacks.Or, "Actually, the earth is small, and the ocean is not an infinite garbage dump."

How it started

The modern use of the term Anthropocene began in 2000 with Crutzen & Stoermer's paper in the Global Change Newsletter, simply entitled “The Anthropocene.” This was followed in 2002 by Crutzen's high-profile piece in Nature (“Geology of Mankind”), which gained much wider circulation and attention.Crutzen is a 1995 Nobel Laureate for research on the ozone hole.

A pivotal event in terms of gaining wider scientific acceptance and adoption was the publication of a thematic issue of Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 2011. This issue covered a range of perspectives, including conceptual and historical antecedents (6), biosphere transformation (10), sediment fluxes (11), and the geological case (12).That issue is 13 March 2011, Volume 369, Issue 1938. It's a very fun issue, plenty to read!

Then the geologists got on board with the idea.

In August 2016 the WGA [Working Group on the Anthropocene] announced... its vote in favor of formal adoption of the Anthropocene. The WGA made a provisional recommendation that the Anthropocene be established as a new geological epoch, with a start date in the mid-twentieth century, around the time of the Great Acceleration.By the way, this is how the Holocene is described:

It is in many ways just another interglacial of the Pleistocene, but it is distinguished by the spread of agriculture and the rapid and highly unusual increase of one species of highly social and environment-transforming ape.Humans are not just a myth...

Who is talking about anthropocene?

Earth System science

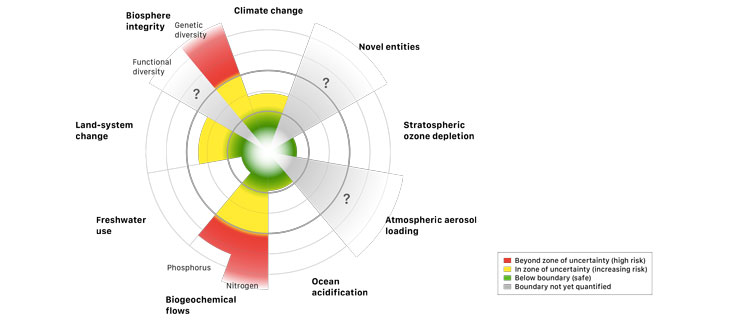

human activity is disrupting many aspects of planetary functions, and moving them outside the modest range of variability that has defined the Holocene, and in a different, warming direction that is (or soon will be) outside of the range of the Pleistocene glacial-interglacial cycles. Most prominent of these disruptions is climate change, but other important disruptions of planetary biogeochemistry include ocean acidification and the greatly increased magnitude of the nitrogen and phosphorus cycles.One famous graph out of this perspective is the "nine planetary boundaries" idea: There are 9 vital signs of Earth, and moving any one of them out of the normal range in the Holocene is going to have major consequences, mostly bad ones.

human domination has led to the emergence of feedback between human and nonhuman systems at a planetary scale, such that actions on energy use, land use, food consumption, and trade have consequences for the basic functioning of the planet and can potentially destabilize planetary function. Human societies have always been closely coupled to environmental conditions at local scales (36), but strong feedback at the planetary scale is a peculiar feature of the Anthropocene and a new challenge for policy and governance.In the start of the Industrial age, Londoners found that they could not just dump their waste into the Thames River. Now, we are discovering that the atmosphere is not actually an infinite heat bath, the ocean is not an infinite garbage dump, and underground oil fields are not actually infinite.

Ecology

A New Pangaea:

(a) Global homogenization of flora and fauna through deliberate and accidental species transferNew energy source put into the biosphere: fossil fuel.

(b) the total amount of biological activity in the biosphere has increased by ∼20% to date, largely because of access to deep-time primary productivity (fossil fuels), a supply of energy that was previously unavailable to the biosphere;It's like humans and their livestocks are drinking some of the crude oil! Indirectly.

(c) a cluster of relatively large species (humans and associated animal domesticates) has been the main beneficiary of this extra energy and has commandeered ∼25–40% of terrestrial primary productivity;Intelligent design, finally.

(d) humans are increasingly directing the evolution of other species;Cyborgsphere?

(e) there is increasing interaction of the biosphere with the technosphere (43, 44).These will leave a big geological mark for hundreds of millions of years.

If humanity disappeared tomorrow, a hypothetical future paleontologist hundreds of millions of years hence would have little problem identifying that something extraordinary occurred, with a wave of extinction and movement of species, and introduction and homogenization of biota that had been previously separated by oceans and latitudes.

Geology

The mystic power of the word "anthropocene" comes from its geological nature. People know that geological phenomena last a long time and over a large area. To think of humans as a geological force is a powerful metaphor.And of course, geologists are considering whether it's actually a geological thing, meaning whether they could see it by looking at the rocks.

The geological debate has tended to focus on whether there is a detectable stratigraphic signature of the Anthropocene.Humans are making new rocks, the most aesthetic of which is the plastiglomerate, made by soil and pebbles held together with molten hardened plastic.

Bricks and concrete fragments in carbonate-cemented beach rock deposits.

To call Anthropocene a proper geological time period, geologists need a geological marker. There are 5 being considered:

- Technofossils: pure elemental aluminum (naturally occurring aluminum are usually oxidized), concrete, plastics (annual production of 0.3 gigatons, about the same as total mass of humans, common in marine sediments as both as macroscopic fragments and as ubiquitous microscopic particles)

- Fuel combustion residues (black carbon, inorganic ash spheres, and spherical carbonaceous particles).

- Other kinds of "disruptions of global biogeochemical cycles", such as increased global prevalence of previously rare elements such as cadmium, chromium, copper, mercury, nickel, lead, and zinc.

- Radioactive fallout from atmospheric nuclear weapons testing in the mid-twentieth century. (This radioactive signal is already used by historians to date human tissue and arts).

- Massive shift in earth's biota, an "ecological reset" comparable in scale as the extinction of nonavian dinosaurs.

Criticism

Some say "anthropocene" is just a fad.

Some say it's too new and political for geologists to discuss.

in being encouraged to adopt the Anthropocene, the ICS is being asked to make a political statement, namely to raise awareness of contemporary human impacts on the Earth system, and thereby potentially encourage a planetary management mindset.

Some say it's too early to tell. Maybe we aren't in the Anthropocene, but the Anthropogene period, or even the Anthropozoic eon. We'd look dumb in the future, much like those "modernists" from 100 years ago seemed too hasty to call themselves "modern", leaving us in the... "post-post-modern age"?

Some say that the word is best left informal, to allow people to adapt it to their own needs and spark conversations. Others object that it'd cause confusion.

Some say it's “a Eurocentric, elite and technocratic narrative of human engagement with our environment that is out of sync with contemporary thought in the social sciences and the humanities.” I really have nothing to say about this, other than that, maybe the humanities need to catch up with the Eurocentric (and soon, Asiacentric) contemporary thought in technoscience and politics.

When is the anthropocene?

The prevailing narrative is converging on a start date for the Anthropocene in the mid-twentieth century, concurrent with the Great Acceleration of human alteration of the planet.Not everyone agrees.

Some say 200 kiloyears ago. Humans caused the extinction of most big animals as they went out of Africa, which caused deep changes in all these ecosystems through "trophic cascade". Trophic cascade is the cascading change due to changing the food web at its higher levels, that is, the apex predators.

Overall, about 162 species of large mammal herbivore and 28 species of large carnivore (about half of all large-bodied mammals) went extinct in this period, with the most severe extinctions being in the Americas. Only in Africa and southern Eurasia, where large animals perhaps had a longer history of adaptation to increasingly sophisticated Homo populations, did many large animal species survive.There is prehistoric blood on human hands...

Humans, incidentally, is now considered the "hyperkeystone species", serving as the ultimate predator species, the ultimate environmental engineer, tying all ecosystems in the world together. The ancient fancies in traditional Chinese medicine can cause extinction of rhinos world-wide.

Some say no. Since human presence is very detectable even in the Holocene, there's no need to put the Anthropocene so early as to replace the Holocene.

Indeed, such an early start might be focussing too much on humans:

Many other animals modify ecosystems at local scales, ranging from mound-building termites to trophic-web controlling top predators; modification of local ecosystems by a social ape is not a sufficient criterion to define a transformative event in Earth history.

Some say it starts with farming, 10 kiloyears ago. Some even think agricultural activities caused enough greenhouse gas emission to prevent Holocene from slipping into another Ice Age, although this is debated.

Some say 2000 years ago,

marked by the occurrence of several well-organized societies (Roman Europe, Han China, the middle kingdoms in India, Olmec Mexico, pre-Chavin Peru) substantially clearing and altering landscapes at regional scale and mining for heavy metals, thereby leaving a distinct stratigraphic record of altered anthropogenic soils

Some say 500 years ago,

the European invasion and colonization of the Americas... The subsequent economic and cultural connection between Eurasia-Africa and the Americas heralded the beginning of a globalized economy, and the Columbian interchange: an exchange of domesticated plant and animals products between the regions (e.g., wheat, rice, cotton, cattle, and pigs from Eurasia; tomato, potato, cassava, tobacco, cacao from the Americas) that marks a key transition in the biosphere with clear stratigraphic legacies.

Some also say 500 years ago, because it's the start of capitalism, and the Anthropocene is really Capitalocene. I find it a somewhat encouraging sign that even its critics can see that capitalism will leave a lasting legacy. Ugly, perhaps, but somewhere, some humans find it beautiful.

Some say in 1945, at the first atomic bomb test, because it's symbolic, and has a very distinctive radioactive signature in the rocks all over the world.

Some say, not yet.

would be deemed to start when and if the Earth system passes a critical transition such as the climate system being tipped into an alternative state and/or the biosphere being degraded sufficiently to mark a mass extinction. This could potentially be in the mid-late twenty-first century. As such, the Anthropocene represents a planetary state to be avoided or steered away from, rather than one to be accepted and managed.

The Technosphere

The unbearable burden of the technosphere (Zalasiewicz, 2018) gives some cool facts to set the mood:

How big is the technosphere? One crude measure is to make an assessment of the mass of its physical parts, from cities and the dug-over and bulldozed ground that makes up their foundations, to agricultural land, to roads and railways, etc. An order-of-magnitude estimate here came to some thirty trillion tons of material that we use, or have used and discarded, on this planet.

Nobody knows how many different kinds of technofossils there are, but they already almost certainly exceed the number of fossil species known, while modern technodiversity, considered this way, also exceeds modern biological diversity. The number of technofossil species is continually increasing too, as technological evolution now far outpaces biological evolution.

One estimate suggests that humans have collectively expended more energy since the mid-twentieth century than in all of the preceding eleven millennia of the Holocene.

The biosphere is extremely good at recycling the material it is made of, and this facility has enabled it to persist on Earth for billions of years. The technosphere, by contrast, is poor at recycling.

Helping the technosphere to achieve autonomy is one goal of mine.

Now onwards to the next paper: Scale and diversity of the physical technosphere: A geological perspective (2016).

We assess the scale and extent of the physical technosphere, defined here as the summed material output of the contemporary human enterprise.

What is the technosphere made of?

It includes the land and the sea. The land includes the cities and the countryside:It includes active urban, agricultural and marine components, used to sustain energy and material flow for current human life, and a growing residue layer, currently only in small part recycled back into the active component.It's big:

approximately 30 trillion tonnes (30000 gigatons), which helps support a human biomass that, despite recent growth, is ~5 orders of magnitude smaller.Recall that the total mass of humans is about 0.3 gigatons.

Here's a boring table that shows just how much human-stuff there is in the world:

The city

The paper is full of geological joke/poetry, the kind where a geologist looks at human-things and describes them in a very odd, geological, but still recognizable way, like a friendly but puzzled alien visitor describing earth:

Buildings – solid, complex but hollow, air-filled structures – following demolition or destruction can be compacted into a solid layer comprising the brick, concrete, glass, metal, plastic, ceramic, wood and other materials used in architecture.War, war has changed... War is now a geological phenomena, the rapid unplanned disassembly of these solid, complex but hollow structures, and their subsequent geological disposition:

This demolition can at times be abrupt and widespread... war-derived rubble in Berlin was redistributed in mounds within the city boundary. Fourteen such mounds still exist, the largest being the Teufelsberg hill (Figure 2), comprising Anthropocene rubble up to 80 m thick...

What is a city in the eyes of a geologist?

... the city is constantly metabolizing with inflows of food and water and outflows of sewage produced by its human component, the latter undertaking constant daily migrations with hydrocarbon-powered vehicles (cars, buses, trains, ferries) or ones powered electrically (mostly trains). The urban technosphere is also evolving year on year as building and demolition take place, in effect operating as an anthropogenically driven sedimentary system with inflow, accretion, erosion and outflow of its component materials, here not powered by gravity or by wind, but mainly by directed energy release from hydrocarbons.I love living in an anthropogenically driven sedimentary system powered by directed energy release from hydrocarbons!

The countryside

The countryside is much less thick or heavy in terms of its technosphere content, but it still has plenty, mostly in its agricultural land use and associated change in biome (the "anthrome").

Underground

The technosphere extends deeply into the subterranean rock mass via mines, boreholes and other underground constructions. These structures are typically temporary conduits for the managed flux of potable water, liquid and solid effluent, hydrocarbons, metals and minerals (and in the case of subway systems the flux of humans themselves).

The authors found it hard to estimate how massive the underground technosphere is, however.

The sea

Other than the obvious ones like submarines, oil rigs, and artificial islands, humans mostly change the ocean by heavy fishing:

The bottom-trawled area of sea floor now extends over most of the continental shelves, and locally out onto the continental slope; this is the submarine equivalent of terrestrial agricultural soils, repeatedly ploughed to depths of some decimetres to scrape up seafood to feed humans, locally triggering sediment gravity flows. Volumes of seawater, too, are systematically fished, now dramatically altering global fish stocks; not easily defined, and not quantified here, these spaces have nevertheless effectively been co-opted into the technosphere.This has deep impact on other things, such as the coral reef (which is a kind of reef, a geological thing):

These processes may effect significant biosphere change, as in reef systems in the Caribbean, where organic waste accumulation has reduced some reefs to a microbial mat state.From 1977 to 2001, coral reefs in the Caribbeans collapsed by 80%.

Air

Bold of a geologist, to talk about air! Buuut air is part of earth, and geology is really about earth.

The atmosphere is a space now continually crossed by aircraft, mostly along specific migratory paths. In this and in other ways (such as providing oxygen for both biological and industrial respiration, wind for turbines, and passage for radio waves) it may be regarded as an enabling medium for the technosphere, rather than a component of it per se.Humans control a rather big volume of air, turns out:

A specific component is internal air in buildings, modified and controlled for temperature and humidity, across a global stock of buildings now covering >150 billion m$^2$.

But the most significant effect of humans on air is greenhouse gas emission, due to massive oxidization of hydrocarbon (aka "burning oil for fuel") and agricultural metabolism, among others.

as gas at atmospheric pressure, the equivalent of a pure CO2 gas layer ~1 m thick around the whole globe (and now thickening at the rate of ~1 mm every two weeks).

Space

The technosphere, since 1957, has extended beyond the atmosphere into outer space in the form of satellites and related debris orbiting the Earth, and spacecraft elsewhere in, and occasionally heading beyond, the Solar System.

Technofossils

The technofossils are exceeding bio-fossils in diversity:Assuming an average species-span is ~2–5 million years, then the halfbillion years of the Phanerozoic Eon has seen the passage of about 1 billion metazoan species. Of those, only something like 300,000 have been described and named – less than one in a thousand. Why? Many were soft-bodied, and so unlikely to fossilize, and others were simply rare...

If assessed on palaeontological criteria, technofossil diversity already exceeds known estimates of biological diversity as measured by richness, far exceeds recognized fossil diversity, and may exceed total biological diversity through Earth’s history.For example, books!

One commonly produced potential technofossil is the book, and a recent Google-based assessment of titles revealed ~130 million individual titles... each title nevertheless can be regarded as a distinct, biologically-produced morphological entity with its own specific pattern of printed words, pages, dimensions and texture.What would book fossils look like?

... rectangular carbonized masses classifiable by size and relative dimensions and subtle variations in surface texture; fragmentary details of the print information will only be rarely preserved, as are fragmentary details of DNA structure in some exceptionally preserved ancient fossils today.The answer is clearly preservation of books by amber! Or writing things in stone.

A more recent, ‘fossilizeable’ example comprises mobile phones, commercially available since 1983, and with ~6.8 billion unique mobile phone connections made by 2014, operating via hundreds of ‘technospecies’ with complexity of both external and internal structure, of good fossilization potential.Mobile phone fossils!

Now, let's take a deeper look at the technofossils, in The technofossil record of humans (2014). Again, unintentional joke/poetry abound!

The origin and diversification of metazoans has produced relatively few new mineral types over and above inorganic mineral species... Humans, by contrast, produce artefacts from materials that are either very rare in nature (uncombined iron, aluminium and titanium) or unknown naturally (uncombined vanadium, molybdenum). There is a wide variety of novel minerals such as boron nitride, tungsten carbide and ‘mineraloids’ such as artificial glasses and plastics.

Turns out it's the Museum of Modern Geological Formations!

Most trace fossil-formers produce a single type of trace, though some may produce a small number of different types (e.g. trilobite species that produce at different times both Cruziana walking traces and Rusophycus resting traces). The number of different types of potentially preservable human artefacts, by contrast, numbers in the millions, as a result of cultural evolution, and is growing daily.The following paragraph reminds me strongly of Geoffrey West's work on the scaling law of cities: the bigger cities get, the faster they pace, in direct opposition to biological organisms.

The accelerating pace of technofossil evolution correlated strongly with increases in population, not only globally, but also within specific cultures. It is in direct contrast to the pattern classically seen in biological evolution, where the most rapid evolution typically occurs in small isolated populations, with larger populations remaining more stable.

The last century, too, has seen the extension of humans to great depths in the crust, as mining activities commonly reach hundreds of metres into the ground, and drilling operations penetrate to several thousands of metres. This deep crustal penetration by the metazoan biosphere is without precedent in Earth history.Now you know what is human mining: deep penetration by the metazoan biosphere! These human bore-holes would leave long-lasting fossils.

... the deep crustal traces have extremely high preservation potential (until the rocks affected are carried to the surface and eroded, or until they are affected by mountain-building processes so that borehole traces, for example, are obliterated by high-grade metamorphism).In contrast, airplanes can only be preserved through rapid unplanned disassembly:

The constructions that travel through the atmosphere, by contrast, are only rarely preservable, for instance as aeroplanes that crash into the sea.And of course, not even space is safe from the geological force that is humanity:

In the case of extraterrestrial satellites and landing-craft, some are now distributed among other planets and moons, while there is much currently human-made space debris in orbit. The technofossils left on our Moon, at least, having also very high preservation potential. This phenomenon marks a new transition in the history of not just the Earth, but of the Solar System.Technically, technofossils are all trace fossils of humans, thus could be termed "Homo sapiens ichnosp.", but that's too generic to be useful. Rather, we should consider a classification of technosphere species, just like the classification of the biological world into species.

For instance, a toothbrush may be regarded as one type of artefact, within a wider category of brushes and brooms. Collectively, these are all cleaning traces... while some categories of traces may have clear ichnological (and therefore wider biological) counterparts, others may be more or less uniquely human – for instance, the technofossils that we build for recreation (tennis rackets, concert halls), and where novel categories may be needed.Tennis rackets as technofossils... gosh.

What is the biosphere like in pure weight?

Recall that the total mass of humans is about 0.3 gigatons, and the total mass of the technosphere is at least 30000 gigatons.

This news report has a good visualization of all of biosphere in weight. It's based on The biomass distribution on Earth (2018).

It counts only mass of carbon, not all body mass. So that's why it says humans have only 0.06 gigatons of carbon, rather than 0.3 gigatons of mass.

Notice how livestock outweights humans. In fact, the explosive growth of chicken population has made some scientists propose the modern broiler chicken fossil as the definition of the Anthropocene. From The broiler chicken as a signal of a human reconfigured biosphere (2018):

Modern broiler chickens are morphologically, genetically and isotopically distinct from domestic chickens prior to the mid-twentieth century.

Human-directed changes in breeding, diet and farming practices demonstrate at least a doubling in body size from the late medieval period to the present in domesticated chickens, and an up to fivefold increase in body mass since the mid-twentieth century... Broiler chickens, now unable to survive without human intervention, have a combined mass exceeding that of all other birds on Earth; this novel morphotype symbolizes the unprecedented human reconfiguration of the Earth's biosphere.

"I'm fat, and I also have big bones."

Behold the beautiful, massive industrial death machine. Every year, for every human alive, 10 chickens are killed, as well as 1/5 pigs, and 1/25 cattles.

The new chicken is sick to the bones, and fully reliant on humans:

If left to live to maturity, broilers are unlikely to survive. In one study, increasing their slaughter age from five weeks to nine weeks resulted in a sevenfold increase in mortality rate: the rapid growth of leg and breast muscle tissue leads to a relative decrease in the size of other organs such as the heart and lungs, which restricts their function and thus longevity. Changes in the centre of gravity of the body, reduced pelvic limb muscle mass and increased pectoral muscle mass cause poor locomotion and frequent lameness. Unlike most other neobiota, this new broiler morphotype is shaped by, and unable to live without, intensive human intervention.

No comments:

Post a Comment