Heaven and Earth are not kind.

They regard all things as straw dogs.

The sage is not kind.

He regards people as straw dogs.

-- Laozi, Tao Te Ching, Chapter 5

A quick YouTube search shows the usual genocides (here, I include massive man-made death-events) being covered: Hitler's genocide, Khmer Rouge genocide, Armenian genocide, Rwandan genocide, the Soviet famines, the Great Leap Forward famines... but nobody, I repeat, nobody has done a video on Zhang Xianzhong, the genocidal dictator of Sichuan in the 1640s. Indeed, the English information on Zhang Xianzhong is extremely scanty.

Well, not anymore. I will make a video all about Zhang Xianzhong. This post is my scrape-book as I do the research.

The chaos of Ming-Qing transition

The empire, long divided, must unite; long united, must divide. Thus it has ever been.

---- First line of the Chinese epic, Romance of the Three KingdomsA lot of the Western conceptions of the "old and sickly China", with mandarins, long braids, opium-smoking, and ling-chi, those are from the Qing dynasty (1644 -- 1911). Before that, there was the Ming dynasty (1368 -- 1644).

China was extremely powerful during the Ming dynasty, and the seven massive voyages of Zheng He took place from 1405 to 1433, asserting dominance for the Chinese emperor all over the coast of Indian Ocean.

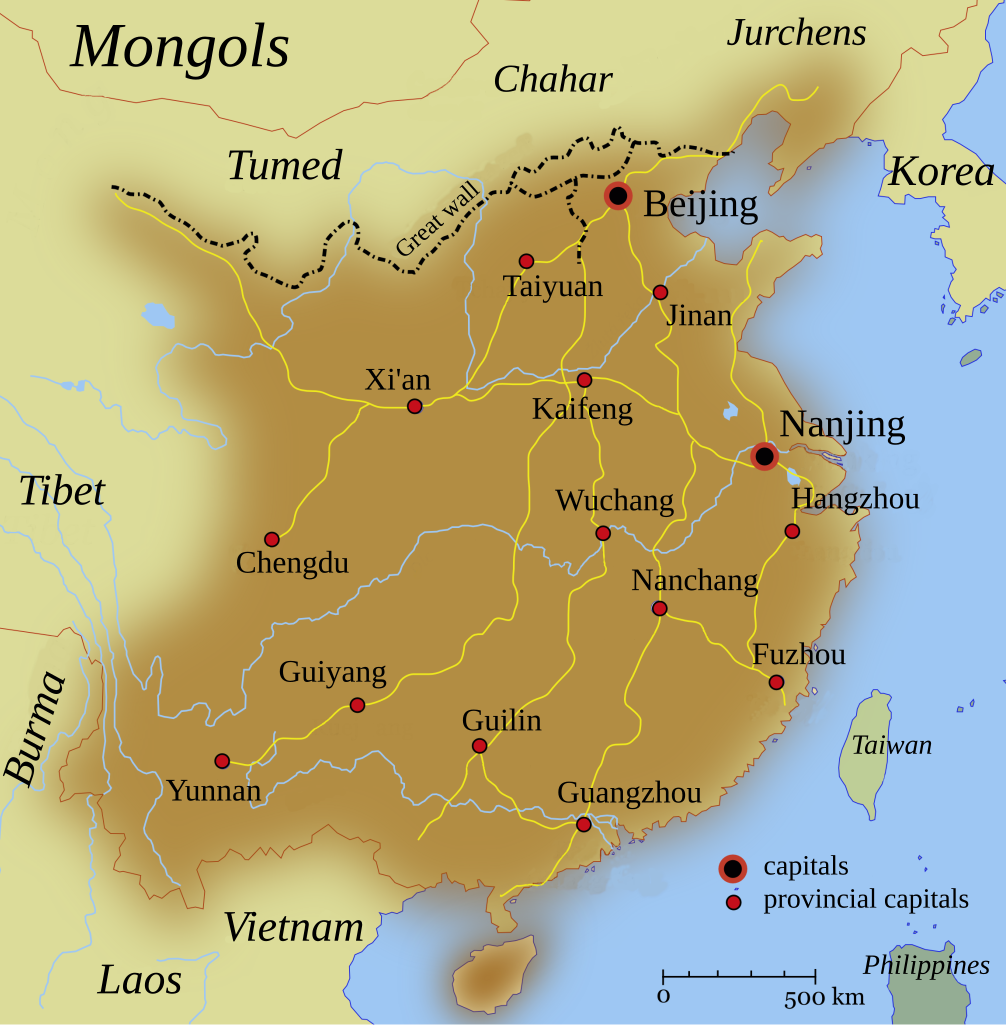

Source: Wikipedia

- Han Chinese loyalists: forces loyal to the Ming government;

- Han Chinese rebels: the many, many peasant rebellions inside China, among whom the most successful two were Li Zicheng (of Da Shun 大顺 empire) and Zhang Xianzhong (of Da Xi 大西 empire);

- Foreign invaders: the foreign Manchu forces from the north, who eventually achieved total victory and began the Qing dynasty.

A rough map of the situation in 1644.

Source: Wikipedia

The rough order of events was as follows:

- The Ming government rotted slowly, and people became discontent;

- The Manchu people in the north organized themselves into a powerful kingdom and dreamed about taking over all of China;

- Chinese peasant rebellions grew bigger;

- Ming government was unable to deal with the rebellions and the Manchu forces at the same time, and collapsed;

- In 1644, Li Zicheng captured Beijing, ending the Ming dynasty.

- A few months later, Manchus captured Beijing, beginning the Qing dynasty. Li Zicheng died soon afterwards.

- In the mean time, Ming loyalists kept fighting in the south, losing more and more ground. The last remnants of Ming loyalists were finally defeated, in Taiwan, 1683. (This reminds me of how the Chinese Nationalists escaped to Taiwan as the last stronghold. However, unlike the Ming loyalists, the Chinese Nationalists are thriving, 70 years on.)

Bonus fact: climate change is to blame

This chaotic period between Ming and Qing matches neatly with the European "Crisis of the 17th Century". Both China and Europe suffered massive wars and population decline during the 17th century.

Perhaps the climate was to blame. From Zhang, David D., Harry F. Lee, Cong Wang, Baosheng Li, Qing Pei, Jane Zhang, and others, ‘The Causality Analysis of Climate Change and Large-Scale Human Crisis’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, (2011), <https://doi.org/10/b6g6mh>:

cooling from A.D. 1560–1660 caused successive agro-ecological, socioeconomic, and demographic catastrophes, leading to the General Crisis of the Seventeenth Century.

Indeed, as a paper in the Science magazine concludes by a metaanalysis, climate has a very strong influence on human violence. From Hsiang, Solomon M., Marshall Burke, and Edward Miguel, ‘Quantifying the Influence of Climate on Human Conflict’, Science, (2013):

The magnitude of climate’s influence is substantial: for each one standard deviation (1σ) change in climate toward warmer temperatures or more extreme rainfall, median estimates indicate that the frequency of interpersonal violence rises 4% and the frequency of intergroup conflict rises 14%. Because locations throughout the inhabited world are expected to warm 2σ to 4σ by 2050, amplified rates of human conflict could represent a large and critical impact of anthropogenic climate change.

Expect intergroup violence to rise by 30-50% by 2050!

Who is Zhang Xianzhong?

From Encyclopedia Britannica:

- He was born in 1606 in Shanxi.

- After a famine in 1628, he became a bandit leader that grew stronger over time.

- In 1644, Zhang led about 100,000 men into Sichuan, and enthroned himself as 大西国王 (“King of the Great Western Kingdom”). His kingdom is ca

- He tried to set up a civil government, coined money and set up an examination system to recruit talented men, but it failed, and he resorted to ruthless terror and genocide.

- In late 1646 and early 1647, Qing forces killed him and defeated his troops.

Zhang is nicknamed "Yellow Tiger" 黃虎, because people thought he had "the jaws of a tiger". As stated in 明史 (History of Ming),

獻忠黃面長身虎頷,人號黃虎。性狡譎,嗜殺,一日不殺人,輒悒悒不樂

Xianzhong is yellow-faced, long-bodied, and tiger-jawed. People call him "yellow tiger". He is cunning, loves killing, and gets upset if he hasn't killed in a day.

One must be careful about such historical sources. For example, History of Ming is written by a Qing official historian, and obviously, such a book would be biased against everyone who resisted Qing rule.

What is Sichuan?

Sichuan is a region of China, where the Yellow Tiger made his kingdom, the place of the massacre. But why Sichuan? Because geography.

Take a look at this map of Chinese topography, with rough location of Sichuan circled.

We can see that it's basically a basin cut off from the vast plains of Chinese heartland. As such, during times of war, it has often been used as a natural fortress for some local king to settle in comfort, while the more ambitious ones fight for dominance of the heartland. It has also been used as a strong base for eventually conquering the Chinese heartland, as the founder of Han dynasty did.

And that's exactly what the Yellow Tiger did during the Ming-Qing wars.

Story of the Yellow Tiger

After reading about him for two days, I can tell the story of Yellow Tiger dramatically, if not rigorously. For rigorous details with citations, refer to the two sections below.

Pop quiz: what are "heavenly candle"? Are they

- A, stars, or

- B, hot air balloons, or

- C, piles of human feet covered in wax and also on fire?

The answer is of course C! Whaaaat?

So have you ever heard of the phrase "Crisis of the 17th Century"? Compared to the century before and after, the 17th century was a time of chaos in Europe. There were the Thirty Years War, the English Civil War, the Eighty Years War... But what's less known is that China fell into an even deeper hole during the same period. The Ming dynasty gave way to the Qing dynasty, and during the transition, what with wars, famines, and all, over one in three of the 160 million Chinese people died.

The Ming dynasty had ruled China since 1368, but at the start of the 17th century, it was in deep troubles. Just to the north of Beijing, the Jurchens were unifying into a strong empire. In its heartland, crops were failing due to a temporary drop in temperature known as the Little Ice Age. The end was coming for Ming, and in 1644, the vast armies of Qing would capture the capital city of Beijing.

Ming Empire,1580. Source: Wikipedia

And out of all those who tried their luck during this chaotic times, none could compare with the peasant rebel Zhang Xianzhong.

In 1606, Zhang was born in a peasant family in 定边 Dingbian, 陕西 Shaanxi. He was tall, with a yellow face and bushy eyebrows, a beard more than a foot long, and a thunderous voice. Because of this, he got the nickname "Yellow Tiger".

In 1628, a massive drought hit Shaanxi, but the Ming government was too busy fighting the Jurchens to help, and to make matters worse, they cut off the postal service in Shaanxi, which was a major source of income for the local folks.

Well, if there ever was a time to go postal, this was it. In 1630, Zhang joined a peasant rebellion and started pillaging the countryside like good rebels do. The next ten years was a fun time fighting Ming, surrendering to Ming, fighting Ming again, mainly in the 湖广 Huguang regions, as his army grew from a few hundred to over a hundred thousand.

In 1641, we have the first records of his extreme sadism. When he captured 六安 Liu’an, he

severed all the right arms of the men and the left arms of the women so that couples would have a matched pair in his twisted sense of humor.

But that was just the beginning.

After years of raping and pillaging, the Huguang was no longer very profitable, so Zhang looked west to 四川 Sichuan. Now a quick geography lesson. Here, the red circle is Sichuan. What do you see?

We can see that it's a basin cut off from the vast plains of Chinese heartland. As such, during times of war, it has often been used as a natural fortress for some local king to settle in comfort, while the stronger kings fight for dominance of the heartland.

1644 was a time of massive change. Beijing was sacked by another peasant rebel 李自成 Li Zicheng. The last emperor of Ming hanged himself. Then the Qing forces sacked Beijing again and Li Zicheng died shortly afterwards. While all these were going on, the Yellow Tiger sacked 成都 Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan in October, and called himself 大西王 Great West King.

The Great West King would lose everything and die in two short years, but these two years were one of the bloodiest in human history.

Now, when normal people is suddenly given absolute power, they might enjoy some decadencies, like ice cream with gold leaves and caviar. But the Yellow Tiger was a paranoid, schizophrenic, psychopathic king, and that means it's horror story time!

Once, he got malaria, and spoke to heaven: "I will dedicate two heavenly candles when I recover." After he recovered, he commanded his soldiers to cut women's feet and pile them up into two foodfoot pyramids. They are then covered in wax and burned.

His paranoia also drove him to create a police state worse than 1984. Everyone must keep watch of people within ten doors to their home, and report any suspicious activities. Having a bit of money would get your body parts cut off, and more serious crimes would get you decapitated, dismembered, or flayed alive. People were afraid of doing anything. No talking, no laughing, no cooking after dark, it was like they were dead before they were even killed.

He used many execution methods, from decapitation to burning alive, to slow slicing, to flaying alive, his favorite method, sometimes even dumping partially flayed but still living victims into city streets to beg for help.

A bit of history: the first emperor of Ming really enjoyed killing corrupt officials. Taking more than 60 taels of silver, which is the yearly salary of a mid-level official, was enough to get one killed, and many of those were flayed afterwards, stuffed with straw, and put outside of government buildings to gently encourage others to be clean.

Zhang held a few exams to select officials for his government, except the last time, instead of examining them, he "processed" them from the east gate to the west gate like pigs to sausages. Then he did it again.

Now Zhang might hate the scholars, but he found it useful to make some poems here and there, like the famous 七杀碑 Seven Kill Monument.

天生萬物以養人

人無一善以報天

殺殺殺殺殺殺殺

Heaven brings forth innumerable things to nurture humans.Although the real version is somewhat tamer:

Humans has nothing good to thank Heaven with.

Kill Kill Kill Kill Kill Kill Kill

天生万物与人,人无一物与天,鬼神明明,自思自量。

Heaven has given myriad things to humanity.But if we take a closer look at the poem, we will see the true nature of Zhang's ideology of genocide. Zhang considered himself a scourge of heaven, and it was his heavenly mission to kill all the evil Sichuan people. In his own words,

But humanity has offered nothing to Heaven or Earth.

The gods and spirits know this clearly.

Ponder this and measure yourself!

I am a star from a higher world; the Jade Emperor has sent me down into this world to slaughter these wicked beings.On January 8, 1646, Zhang declared that all people in Chengdu, his very own capital, would be killed. In one legend, when Zhang was about to kill the citizens of Chengdu, there were three claps of thunder. Zhang shouted to the heavens: “ You have sent me down to kill people - why do you now frighten me with thunder?" - and he fired guns back at the heavens.

The corpses filled the rivers, turning them red, and it rose several feet. A few days later, he executed all his court officials that came from Sichuan. He then sent his armies into the countryside to exterminate all Sichuan people, and promotions were priced in body parts. For example, 200 pairs of hands and feet for squad commander.

Big shipments of body parts went into Chengdu, and they are sorted by types in front of Zhang's palace, which was already decorated with the skins of people he flayed alive.

It seemed that the psychosis has fully set in at this point, and Zhang saw disembodied hands snatching food from his plate, headless female ghosts playing instruments, and heard the howls of hundreds of dogs shaking the earth.

By the end of 1646, he has exhausted Sichuan, and the Qing forces were coming. So he gathered up his army, abandoned Chengdu, and went east to repel the Qing forces. He was killed by an arrow on the morning of January 2, 1647.

Now, take a deep breath, and count the dead.

The official historians of Qing claimed he killed over 600 million people, which is 4 times the population of China at the time. Modern historians think that he "only" killed 600 thousand people, which was 1 in 10 Sichuan people.

How does this compare with some other genocides? Hitler's genocide killed 2 in 3 European Jews. The Cambodian genocide killed 1 in 5 Cambodian people. In comparison, the Yellow Tiger did not seem so bad. However, none of them could compare with him in creative sadism.

Follow the Yellow Tiger

This section is a long digest of the book On the Trail of the Yellow Tiger: War, Trauma, and Social Dislocation in Southwest China during the Ming-Qing Transition, (Swope, 2017)

(Page 10) On how many people died during the Ming-Qing transition.

China’s population is estimated to have dropped by as much as 50 million between 1600 and 1660. And since Sichuan and the southwest in general were the areas most affected by the crisis and generated some of the richest primary source literature, this is an ideal lens through which one can study the local effects of the global and national processes.

According to A Brief History of China’s Population (Banister, 1992), in 1749, well after the stability of Qing dynasty, the total population of China was still just 177 million, a population drop of 50 million would mean that around 1/3 of people died during the years of chaos.

(page 11) The Ming-Qing transition period was full of written records, from all angles, including written accounts by Ming and Qing officials, and local literati and aristocrats, and even accounts by European missionaries Lodovico Buglio and Gabriel de Magalhães. By combining all these accounts, their biases can be cancelled out, and the truth revealed.

(page 18) Zhang was born in 陕西 Shaanxi. Since he was a peasant, his upbringing was only recorded in legends.

The most famous story concerns an incident in Sichuan province wherein his father’s donkey relieved itself outside the home of a local literatus. When the notable came outside, he stepped right in the feces. So he beat Zhang’s father and ordered him to clean up the mess with his hands. Zhang allegedly vowed to return one day and kill everyone in the town, a promise he reportedly kept. Some point to this story as the origin of Zhang’s enmity toward the Sichuanese people.(page 19) Why he was called "Yellow Tiger".

Zhang was tall, with a sallow complexion, possibly due to a childhood illness, and bushy eyebrows. He also had a full beard, more than a foot long. It was allegedly because of his appearance and thunderous voice that people began calling him the Yellow Tiger from a fairly young age.(page 22) In 1628, a massive drought in Shaanxi caused famine, but the Ming government did not help, and even stopped the postal service in Shaanxi, which was a major source of livelihood for folk in this region.

Thus those who became peasant rebels were a mix of starving peasants, mutinous troops, desperate conscripts, and laid-off postal workers, many of whom had rudimentary military skills.Time to go postal!

One of the rebels was Zhang, who managed to gather more followers over the years.

(paeg 28) In 1635, the rebels convened at 荥阳 Xiangyang to organize themselves better against the increasing Ming threat. They decided to fight east.

Zhang achieved symbolic victory by sacking 凤阳 Fengyang, home of the ancestral tomb complex of the Ming founder. He desecrated the tombs and burned the palace complex.

Though not necessarily significant in a strategic sense, the destruction of Fengyang was a tremendous blow to Ming royal prestige, and the emperor was forced to perform special ancestral sacrifices and wear mourning garb. The surviving government officials responsible for defending Fengyang were executed by order of the Ming court.(page 33) Zhang trolled Yang, the Ming official in charge of fighting Zhang:

杨嗣昌 Yang Sichang put a bounty of 10,000 taels on Zhang’s head, to which Zhang responded by putting a bounty of three taels on Yang’s head, the note appearing on Yang’s own office wall!

(page 36) Zhang managed to threaten Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan. He has also started marauding the Huguang region, often massacring the cities he sacked.

(page 36) In 1641,

Zhang’s penchant for committing atrocities also continued. When he captured Liu’an, he severed all the right arms of the men and the left arms of the women so that couples would have a matched pair in his twisted sense of humor.This is from 张献忠陷庐州纪 (The Record of how Zhang Xianzhong Sacked Luzhou):

午后,将六安人尽剁其手。先伸左手砍去,不算,复剁其右手(page 38) tactics of Zhang:

Zhang liked an ideal ratio of 7:3 between cavalry and infantry and placed a premium on acquiring mounts, preferring each of his soldiers to have two. He preferred using his cavalry as a spearhead so they could exploit enemy formations and retreat and extract themselves from danger if needed. He would use feigned retreats to lure enemies into ambushes of spearmen. Like most late Ming commanders, Zhang favored a ruthless discipline, executing men for desertion in battle and flogging soldiers for all manner of petty offenses. According to some sources, he even fed his horses human blood.(page 39) In 1643, Zhang, leading over 100,000 troops, has become an existential threat to Ming. He started pushing west, upstream the Yangtze River, considering setting up his own kingdom, and calling himself 西王 King of the West.

(page 41) Zhang sacked 武昌 Wuchang (modern Wuhan), and made it the "west capital" of his kingdom. He called himself 大西王 Great King of the West,set up a bureaucracy, held an exam, and started state-building (spoiler alert: unsuccessfully).

(page 43) Zhang became a decadent emperor

women were often subjected to his rages. One incident involved feeding a number of prostitutes to dogs. Another infamous incident involved Zhang severing the feet of his concubines and covering the feet with wax to make a “heavenly candle.” In addition to his predilection for pretty girls, some sources reference Zhang’s interest in surrounding himself with handsome young boys, and it is possible he was bisexual.In original Chinese, from 彭遵泗 Peng Zunsi 蜀碧 Shubi:

张献忠据蜀时,偶染疟疾,对天曰:‘疾愈当贡朝天蜡烛二盘。’众不解也。比疾起,令斫妇女小足堆积两峰,将焚之,必要以最窄者置于上,遍斩无当意者。忽见己之妾足最窄者,遂斫之...

When Zhang Xianzhong was occupying Sichuan, he got malaria, and spoke to heaven: "I will dedicate two heavenly candles when I recover." Nobody understood that. After he recovered, he commanded his soldiers to cut women's feet and pile them up into two peaks, with the smallest on top. Women were being chopped all around, but he could not find one he wanted to top the peaks. Suddenly he saw the smallest feet from his own concubines, and had that chopped...He was then driven away from Wuchang by Ming forces.

(page 47) Zhang decides to move to Sichuan.

the constant warfare of the previous several years had seriously affected the productive capacity of the province. Zhang’s armies may have approached half a million by this point, and he was concerned about feeding them. After some debate among his leaders, he decided to move west into Sichuan, which, despite its recent troubles, still had the reputation of being “Heaven’s Storehouse.” [天府之国](page 58) It was 1644. Li Zicheng has sacked Beijing. The last emperor of Ming hanged himself. Zhang is ready to besiege Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan.

For several times, the local princes of Ming refused to spend money on defenses, and got killed after their cities were sacked by Zhang. Their excuses were usually based on the Ancestral Injunctions, which forbade them from meddling with government or military affairs.

The local prince at Chengdu certainly didn't help.

The fall of Chengdu was quick, and Zhang entered the city. He proclaimed the start of 大西 Da Xi dynasty on 1644.10.06.

(page 68) Zhang got spooked.

He was then accosted in the street by a dirty Daoist mendicant. His aides tried to shoot the man, as did Zhang himself. The adept caught the arrow and spooked Zhang’s horse, sending the bandit leader toppling to the ground. He then escaped down an alley. Li Dingguo told Zhang not to fret about the incident, saying that the man was a well-known local mystic who barked like a dog all day and was crazy but harmless.(page 69) Zhang killed a lot of women

So was a pretty young virgin named Xu Ruojing, and Zhang hoped to enjoy both in his first two nights in the palace. Zhang held a great banquet the first night and got very drunk. He told Xu that he planned on making her his empress. She thanked him and offered him another cup of wine. She then tried to clock him with a silver decanter, but Zhang recovered from the blow and cut off her right arm. She then tried to beat him with her left hand, so he cut off that arm too. She fell to the ground still cursing him. The episode later became the subject of a Qing dynasty folktale called “Hitting with a Silver Chalice.” Taking another drink, Zhang complained, “I had no idea the women of Shu were all so evil. Bring forward the prince’s women and kill them!” All but the youngest, prettiest virgin were killed, but she later killed herself. Zhang cut all the bodies up.

(page 73) A daring escape

The most dramatic account pertains to the capture of General Yang Zhan. He was also apprehended and offered a post, but refused, so for reasons not specified in the sources, Yang was led outside the city to be executed. Yang was wearing fancy armor, and apparently the rebels asked him to remove it so they could have it. Yang replied, “I don’t care about my life, so why should I care about my clothes? You can have my armor when you fish my body out of the river.” As they moved to forcibly remove his armor, Yang grabbed a dagger from one of his captor’s hands, stabbed the man, and made his escape by diving into the Jin River.¹³⁹ The Ming military official Cao Xun made a similar escape by diving into the river. Yang would subsequently become the leading figure of the Ming restoration movement in Sichuan.(page 77) Zhang set up a brutal regime

Districts were organized into mutual responsibility (baojia) units and were expected to inform the authorities of seditious talk or activity. Failure to do so could result in death for the offenders and those families residing within ten doors on either side of them. The lightest offenses got one flogged, like citing Ming precedents, entering through the wrong door, or facing the wrong direction in a court audience. Slightly greater offenses like hoarding small amounts of wealth were punished by cutting off ears, noses, hands, or feet. Moderate offenses were punished by simple decapitation and more serious ones by a slow death, usually by slicing or dismemberment, with the most serious offenders being flayed alive. It was said that the outer walls of Zhang’s palace were “decorated” with the flayed skins of offenders and that piles of severed body parts, divided by type, amassed in front of his residence. Zhang’s predilection for flaying people supposedly derived from his admiration of the Ming founder, Hongwu, who used the same punishment against traitorous ministers.(page 81) The real version of the legendary seven-kill poem.

天生万物与人,人无一物与天,鬼神明明,自思自量。

Heaven has given myriad things to humanity.(page 91)

But humanity has offered nothing to Heaven or Earth.

The ghosts and spirits are brightly luminous.

You should ponder this deeply.

Whatever Zhang’s true intentions for the administration of Sichuan and the establishment of a viable kingdom, matters were spiraling out of his control within a month of his enthronement. His response to the increasing pressures was both predictable and tragic. The events of the next two years would go down in the annals of Chinese history as some of the bloodiest ever, and in Sichuan Zhang would earn the moniker of “The Butcher”... That phase would begin outside of Sichuan, as the province was to be thoroughly despoiled from 1645 through 1649. Long lauded as “Heaven’s Storehouse,” Sichuan became a charnel house...(page 93) Paranoia, police state.

Damaged passes and missing curfews could be grounds for execution. This created a general atmosphere of terror in the streets.(page 103) Zhang claims to be the scourge of god:

Zhang also became more fixated on his divine mission to slaughter. He claimed to receive directions from a “divine book” (Tianshu) that only he could read and understand. Zhang ranted, “There are too many commoners in China, and their wickedness is unchecked. Therefore the Lord of Heaven has sent old Zhang to the world to kill people. . . . I want to fulfill the charge of Heaven, so my plan is to kill all the evil people in China.”(page 104) Zhang's paranoia, schizophrenia, psychopathy, sadism:

possibly suffering from paranoid delusions. His frequent references to visions and voices may indicate schizophrenia. His apparent delight in torture also suggests that he was, in modern terminology, a psychopath. For Zhang not only liked killing, he delighted in various forms of torture. He is most infamous for flaying people alive, sometimes even dumping partially flayed but still living victims into city streets to beg for help. But he also killed people by slow slicing (up to a thousand cuts), firing squads, water torture, driving nails through hands, roasting people alive, cutting off their genitals and/ or breasts (women), flogging, and crushing people to death.

Moreover, he apparently delighted in watching people being tortured, as de Magalhaens reports, “It seems that he ate and drank with greater gusto when people were being skinned alive or being cut up into pieces in his presence and at the same time that the pieces of human flesh were being cut off and dropping to the ground, he would be cutting up and eating the meat on his plate. And while the blood dripped, he drank his wine.”Mountains of body parts:

It was against this backdrop that Zhang commenced his practice of having soldiers submit severed body parts for rewards and promotions. It supposedly started when an underling of Sun Kewang submitted some 1,700 hands on his own initiative. Chengdu became a scene of horror as shipments of hands, ears, and noses started coming in and piling up as shipments of hands, ears, and noses started coming in and piling up around the city.(page 108) Paranoid police state.

There was no exchange among friends, no one visited anyone; even though they were relatives there could be no conversation between two men under pain of being skinned alive immediately. When doors were shut for the night, so were mouths. If a door was left open or a fire kindled in one’s house, if one word were spoken, punishment was swift, not just for the culprit, but for those living in the ten neighboring houses on both sides of the guilty one’s house. Parents accused children and children their parents, and those who did this were highly praised by the Tyrant. If a large group of people were talking together even though there were the mandarins living in the royal palace, spies would immediately arrive on the scene, if they weren’t already there, and ask what was being discussed. This caused such horror and fear that these men no longer resembled living men but mute statues and portraits of death itself.

People were killed for the slightest offenses, like not cutting weeds in their courtyards or miscopying characters in official documents. Common folk said that even smoke coming from one’s house after dark was a sure way of inviting execution. Women were regularly ravaged, sometimes in front of their husbands or children. Porters and eunuchs were killed for not removing the bar on a door in the palace. When a physician’s herbs failed to cure one of Zhang’s executioners, he was cut into tiny pieces, and all other physicians in the city were ordered decapitated. Officials in the Ministry of Justice were killed for failing to report routine travel to Zhang.(page 109) Zhang held official exams, but turns out the exams are more like butchers examining pigs. 5000 - 23000 scholars were killed like pigs going through a sausage factory:

They entered through the east gate and were “processed” out the west gate.

According to some versions of the tale, Zhang gave them a chance to live if someone could write the character for “commander” (帅) sufficiently in large script. One man tried but failed, so he was killed. Bodies were tossed into the nearby river, and their writing brushes “piled up like a mountain” in front of the temple. Only two young scholars were left alive to tell the tale. 欧阳直 Ouyang Zhi, author of 蜀乱 Shuluan, was an eyewitness to the slaughter as he was in Zhang’s service at the time. He maintains that more than ten thousand were killed. Others were tied to horses to be torn apart at the blast of a cannon (which spooked the horses) while the bandits watched laughing.3 months later, Zhang would hold another “examination”, killing another one to ten thousand scholars.

After that, he sent religious people to the chopping board.

Zhang then turned his wrath to Buddhists, physicians, Daoists, and artisans. He told the Jesuits, “Your 天主 Tianzhu, who is the same as Heaven, brought me to Sichuan to castigate the bonzes and other wicked people who were out to kill you.” Buddhists had previously been killed to mark his enthronement, and there were also supposedly incidents at Daci Temple where Zhang invited monks for ordination ceremonies just to kill them. Other sources maintain that people were killed at Daci Temple.(page 111) Zhang explained to the Jesuits that he was the scourge of heaven.

The people of Sichuan did not know Heaven’s Mandate so Heaven abandoned them. Indeed, from ancient times the Lord of Heaven knew of the wickedness of Sichuan’s people so that’s why Confucius was born in Shandong. The people of Shandong love sages and respect the sagely way but the people of Sichuan are not like this. Therefore the Lord of Heaven ordered Laozi to punish the people of Sichuan and every time they act up, they must be punished again. Now the Lord of Heaven has sent me to be the Son of Heaven and exterminate the people of Sichuan so as to punish them for their crimes against Heaven.(page 112) Things got very bad in 1646, and Zhang massacred all of Chengdu.

By the end of the year, a chill wind blew over Chengdu and black clouds descended, presaging even darker days to come. So on the twenty- second day of the eleventh month of 1645 (January 8, 1646), Zhang held a military conference and said that the massacre of the populace of Chengdu would commence the next day. He said, “Not a single person will be spared.”According to de Magalhaens,

The command was carried out immediately, leaving that great and populous city deserted; the widow of its own native people. The river which flowed around it did not seem to have any water in it, only blood. This great river, the son of the ocean into which it empties, was so filled with dead bodies that for days it was totally unnavigable...According to Chinese accounts,

that river was totally red, and it rose several feet up on the city walls. It got so bad that Zhang had to detail men to go on boats downriver from Chengdu to unclog it, and the smell of decay filled the air for ten li around the city.(page 113) Kill all of Sichuan

Within a couple of days after the massacre of the general populace, Zhang summoned all his court ministers, separated those from Sichuan from the rest, and executed them. Chengdu was virtually empty by the end of the year, and Zhang’s armies were fanning out into the countryside. And while he claimed to be preparing to face the Qing, in an eerie analogy to Hitler’s pursuit of the Holocaust over military aims, Zhang seemed to fixate on the extermination of the people of Sichuan over all other goals. Some accounts even claim he had fetuses ripped from the womb and rounded up children for systematic execution.He was really losing his mind at this point, killing his own soldiers. One reason he gave was:

老子只需劲旅三千,便可横行天下,要这么多人做甚!

Laozi need only 3000 horsemen to roam the earth. The fuck do I need this many soldiers for?Psychosis.

Disembodied hands snatched food from his plate. He stalked the palace with his sword drawn and again claimed to see headless female ghosts playing instruments. He later claimed to see ghosts in broad daylight. At other times he heard the howls of hundreds of dogs shaking the earth, but no one around him could hear anything.(page 114)

He “celebrated” the New Year in 1646 by killing some two thousand soldiers because their officer complained about the quality of silk he received as a reward.

(page 115) Zhang started an organ business: human body parts for titles.

Mountains of hands and feet piled up outside Zhang’s palace in Chengdu “like Mount Fenghuang” and rotted without rain to wash them away for nearly three months. Heads, feet, hands, ears, and noses would be stacked in separate piles. Zhang would supposedly sometimes gather the severed heads together for banquets as Idi Amin reportedly did in the 1970s in Uganda.¹⁴⁶ Promotions and ranks were based on the number submitted. Two hundred pairs of hands and feet got one the rank of squad commander. One could be promoted from vice commander to commander by submitting 1,700 pairs.¹⁴⁷ If one soldier killed hundreds in a single day, he could be promoted to supreme commander. Only adults could be counted for the quotas, and women were only half as valuable as men.(page 117) The final casualty figures: From 1644 to 1664, due to war, famine, disease, and other factors, of the 4 million Sichuan people, 2 million died. Out of these, 0.6 million were killed by Zhang's troops.

The modern Chinese scholar Zheng Guanglu [郑光路], who has perhaps done the most careful work in terms of scouring the available traditional sources, estimates that from 1.8 to 2 million people died in Sichuan between 1644 and 1664 out of a total population he estimates at 3 to 3.6 million. The latter figure seems a bit low; the population of Sichuan in this period was likely between 4 and 5 million. And while admitting that Zhang played a major role in this depopulation, Zheng correctly notes the duration and extent of military operations in the province that lasted more than a decade past Zhang’s death. He concludes that around 1 million were killed by direct military operations, and the rest died from starvation, disease, marauding wildlife, and other associated factors. As for the outrageous 600 million people killed by Zhang’s troops, repeatedly mentioned in the Mingshi and many other sources, Zheng finds that 600,000 is a more plausible number by noting how mathematical figures were calculated in traditional sources and pointing out that wan 万, or 10,000, was often substituted for yan 衍, which means “extra” in classical sources.

Also, Astronomy

The two Jesuits in the court of Zhang offers a very interesting angle to this whole event. The fact that the Jesuit account of the event agrees essentially with the many Chinese accounts allows us to conclude that Zhang was really a psychopathic killer that butchered Sichuan.

This section follows Zürcher, Erik, ‘In the Yellow Tiger’s Den Buglio and Magalhães at the Court of Zhang Xianzhong, 1644–1647’, Monumenta Serica, 50.1 (2002), 355–74 <https://doi.org/10/gg5g3c>

First, who are the Jesuits? They are Catholic evangelicals, actively spreading Catholic Christianity around the world. Their historical significance is mostly in their mission in China during the 16-18th century, which allowed a cultural exchange between China and Europe. China learned about the new sciences of Europe, and Europe learned about the old culture of China.

By 1645, Zhang had developed the obsessive idea that Sichuan was a country of rebels and sinners , and that Heaven itself had commissioned him to punish them for their crimes. As a result, he turned to terrorism on a stupendous scale. He had 140 , 000 Sichuanese soldiers disarmed and butchered. He almost exterminated the educated elite as well as the Buddhist clergy. At his own court and in the central government, wanton killing became the rule; people would be condemned to death for the slightest transgression. His troops were sent out all over Sichuan on murderous dragonnades called 草杀, countryside killing. In November 1645, he crowned his work by exterminating all the 60, 000 inhabitants of Chengdu.

Buglio and Magalhães were in Chengdu when Zhang sacked it, and Zhang invited them to his court:

I want you to come to my palace frequently, because I like to talk with you and to ask you many questions about your homeland, as well as about other parts of the world which you have seen and visited.They were given the title 天学国师 National Masters of Heavenly Law, and Zhang used them as astronomers and informers of science, technology, and European history.

During the entire banquet the king asked us many questions about the [Catholic] doctrine, about Europe and about mathematics, and the deep insight, judgment, and wit by which he reacted upon all our answers filled us with admiration.Apparently Zhang thought of himself as a god, and was very interested in astronomy.

In his conversations he showed a remarkable, almost obsessive interest in European “mathematics" (i.e., in this context , astronomy), and that may have saved their lives.By the end of 1645, Zhang has massacred Chengdu and moved out for a last stand against Qing forces. The two Jesuits wanted to run away, so they said to Zhang that they'd like to go to Macao, where they could gather up more astronomy books and reunite with Zhang after he conquered China. Zhang originally agreed, but then had the paranoid idea that it was a conspiracy set up by the Fathers' Sichuanese servants, who intended to rob and kill them on their way to Macao. All except one were flayed alive.

The Jesuits tried to argue but could not save them, and Zhang put them under strict surveillance. In the last days, Zhang commissioned them to

construct a bronze celestial globe in the shortest possible time. They had to work day and night in the tent that served as a workshop , in the unbearable heat of the furnace. Zhang himself urged them on, appearing frequently in the workshop, even in the dead of night (for he hardly needed any sleep). When the globe was presented, it immediately led to a crisis. Some court astronomers held that the inclination of the ecliptic, as indicated on the globe, was a ridiculous mistake, and that this misrepresentation of Heaven endangered the very existence of the empire. For three days the Fathers defended themselves and the principles of European astronomy, but in vain. They were told to return to their tent and to wait for the next day, when Zhang would decide about their fate. Somebody told them that all was lost, and that they had to expect the death penalty.They were lucky that Zhang was killed by a Qing archer on that next day, and they were captured and treated well by the Qing forces. They moved to Beijing and continued their mission there.

Zhang's ideology of genocide

There was an ideological thread behind Zhang's genocide of Sichuan. While Li Zicheng relied on popular support, Zhang relied on only the loyalty of his own troops.Both the Chinese and the Jesuit accounts bear witness to the fact that in his last years Zhang considered himself a “scourge of God", whose mission it was to exterminate the sinful people of Sichuan.

Zhang claimed to be of divine origin, or at least to carry out a divine mission. As he told his ministers: “I am a star from a higher sphere (上界); the Jade Emperor has sent me down into this world to slaughter these wicked beings (造孽众生). And, elsewhere: “I am in charge of killing on behalf of Heaven."In the original Chinese from 流贼张献忠祸蜀记 (Record of Marauding Bandit Zhang Xianzhong's Depredation of Sichuan)

我系上界一星,玉皇差我下界,收此造孽众生An illustrative story, even if not reliable:

when Zhang was about to kill the citizens of Chengdu, there were three claps of thunder (showing Heaven's displeasure). Zhang is said to have shouted to Heaven: “ You have sent me down into this world to kill people - would you now try to frighten me with thunder?" - and he fired guns upward to heaven.The idea that a human could be a star from the heavens is directly taken from Taoism. Indeed, from Chinese sources, Zhang went to 梓潼 Zitong 七曲山 Mount Qiqu and enlarged a temple dedicated to 文昌帝君 Wenchang Dijun. and he composed a poem and a sacrificial text in which he addressed the god as his blood relative. He also worshipped 关帝 Guandi, the god of war.

This can also explain his fanatical interest in astronomy. He apparently made no distinction between the religious heaven in which the Jade Emperor and gods reside, and the physical heaven that astronomers study. European astronomy was far more impressive to him because it can accurately predict astronomical events like eclipses.

When you Chinese tell me that the sun is standing in a certain sign, what proof do I have that you are telling the truth? But they will tell me the exact year, month, day, hour, quarter, and very moment of a solar or lunar eclipse, and when the predicted time has come, everything will happen as they have foretold.

Bonus fact: modern Chinese view on Zhang

I looked at some modern Chinese commentaries on Zhang on the Chinese Internet, and it is very amusing. They are generally either very positive or very negative. The negative comments focus on his atrocities, unsurprisingly. What's amusing is the positive comments.

Why positive? Because the Chinese Communist Party has seen in Zhang, as well as many other historical peasant rebellions, a kindred spirit, and interpreted him as a fighter for the proletariat class against the evil landholding class. As such, the very positive comments focus on the corruption of Ming (monarchical landowners, thus corrupt and despicable for Marxists), the inevitability of historical progress (historical determinism is one important assumption in Marxism), and on the class consciousness of Zhang in taking money from the haves to give to the have-nots.

Appendix: Brief timeline of the Ming-Qing transition

Ming dynasty map. The Jurchens live in the "Nurgan" part. Source: Wikipedia

- 1606: Zhang Xianzhong born in 定边 Dingbian. Li Zicheng born in 延安 Yan'an.

- 1619: Nurhaci united the Jurchen people in Manchuria, and threatens Ming from the north.

- 1628: Drought and famine in 陕西 Shaanxi, but Ming is too distracted by the Jurchens to help, forcing many peasants to rebel.

- 1630: Zhang rebelled in 定边 Dingbian.

- 1635.01: Rebel meeting at 荥阳 Xingyang. They decided to fight east.

- 1635.01: Zhang sacked 凤阳 Fengyang and desecrated the Ming ancestral graves, a great symbolic loss for Ming.

- 1635: 皇太极 Hong Taiji rebranded the Jurchen people as "Manchu people", because "Jurchen" was a name that Ming dynasty used to refer to them, as a vassal state.

- 1636: Hong Taiji proclaimed start of Qing dynasty.

- 1638: Zhang surrendered to Ming forces at 谷城 Gucheng.

- 1639: Zhang rebelled at Gucheng.

- 1640-42: Zhang marauded around 湖广 Huguang regions.

- 1643: Zhang sacked 武昌 Wuchang, proclaiming himself as 大西王 Great West King.

- 1644.02.08: Li proclaimed the start of 大顺 Da Shun dynasty in 西安 Xi'an.

- 1644.04.25: Li sacked Beijing. The last emperor of Ming hanged himself. The Ming loyalists thenceforth gathered under the banner of 南明 Southern Ming.

- 1644.06.05: Manchu forces sacked Beijing. Li escaped back to Xi'an.

- 1644.09.09: Zhang sacked Chengdu.

- 1644.12.14: Zhang proclaimed start of 大西 Da Xi dynasty.

- 1645: Zhang allied with Southern Ming to fight Qing.

Situation in around 1644.11. Source: Wikipedia

- 1645.05: Li either got killed or ran away to become a hermit. Da Shun collapsed.

Situation after Li disappeared. Source.

- 1646: Zhang's kingdom has diminished greatly. He massacred Chengdu before going south to fight Qing.

- 1647.01.02: Qing forces killed Zhang at 西充 Xichong.

Situation when Zhang died. Source.

- 1644-1683: Qing conquered Southern Ming. The last remnants of Southern Ming fell in 1683 in Taiwan.

No comments:

Post a Comment